Almost a novel. Reading time ~ 45 minutes.

According to Wikipedia, the history of the Moldovan town of Ungeny includes about 30 events worthy of mention.

Among them: the arrival of Soviet power in 1917, the departure of Soviet power in 1918, the arrival of Soviet power in 1940, the departure of Soviet power in 1991, and the opening of an art ceramics factory (date unspecified).

With all due respect to Soviet power and art ceramics, there were really only two truly historical events in the town's chronicle, and neither made it into Wikipedia.

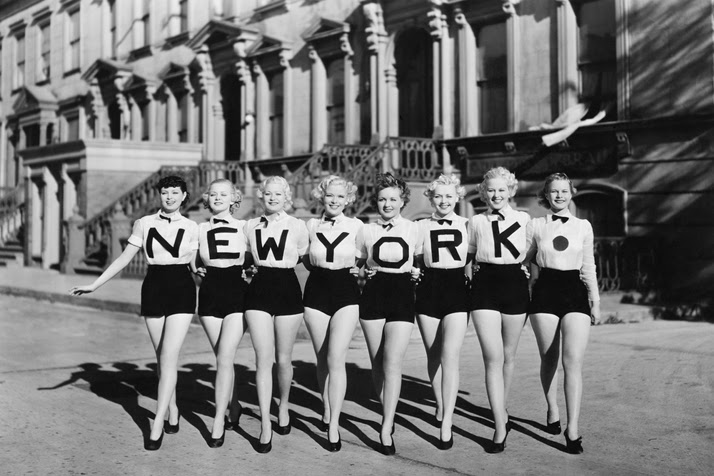

Here they are: On June 27, 1920, a boy named Izek was born to the family of David and Elka Domnich. And in the spring of 1929, the Domnich family relocated from Ungeny closer to Manhattan—to Brooklyn—to improve their living conditions.

In Brooklyn, the Domnichs settled in a wonderful place—Crown Heights—two steps from the subway, near the Brooklyn Zoo, and not far from several private schools, one of which (Boys High School) nine-year-old Izek attended.

For greater respectability, the school teachers "renamed" the boy Isidore, while his father decided the best name for their new life would be Israel.

Izek-Isidore-Israel Domnich, who had begun his education in an Ungeny cheder, didn't falter in New York. He joined the IAL (Interscholastic Algebra League), participated in every imaginable competition, and arrived at his graduation ceremony with seventeen (seventeen!) gold medals from math olympiads in New York, Connecticut, and New Jersey, plus a scholarship from a generous charitable foundation.

The boy with phenomenal abilities was predicted to have a brilliant career. But Izek wanted more. Which is what he did, enrolling in 1938 at Columbia University—one of the most expensive and prestigious private universities in the USA. In the journalism department.

Having boldly dealt with his future career, Izek-Isidore-Israel decided to deal no less boldly with his own name. Leaving Izek in Ungeny, Isidore in Brooklyn, and Israel in his birth certificate, he became simply Izzy or Izy (he wrote it as EZ) in public.

But even Izzy wasn't enough for him. He wanted more. In the Columbia Daily Spectator newspaper, witty publications appeared under the modest signature I.A.L. Diamond ("Diamond of the Interscholastic Algebra League"). He was also editor of the humor magazine and screenwriter for the university variety show Varsity Show, whose concept was successfully "adopted" by Soviet television twenty years later under the name "KVN".

His academic aspirations were equally bold: Izzy planned to earn two degrees—bachelor's in journalism and master's in engineering.

But even that wasn't enough. Easily and cheerfully handling academic overload, magazine editing, work on the Varsity Show, and regular publications in the "Spectator," Izzy became so famous that in 1941 he got a position and column in the New York Times and an invitation to Hollywood as a staff screenwriter.

Domnich celebrated his coming of age by signing a contract with Paramount Pictures, worked there for three years as a regular screenwriter, and never once saw his name in the credits.

That wasn't enough, and Izzy moved to the famous Universal studio, where he lasted a year and achieved his first success: his screenplay "Murder in the Blue Room" was filmed.

With fresh success in hand, Izzy left Universal and moved to the no less famous Warner Bros, where two new successes awaited him—the films "Never Say Goodbye" and "The Girl from Jones Beach," where a certain Ronald Reagan got his first leading role.

But even that wasn't enough: from Warner, Izzy went to XX Century Fox, where five more years of wild success and the highest fees awaited him.

In total: a cheder in Ungeny, private school in Brooklyn, seventeen gold medals from math olympiads, the best university in the USA, fifteen years of a "thermonuclear" career in Hollywood, fame, status, reputation, money, authority, and enormous professional experience. But! This wasn't enough for Izzy.

In 1955, Domnich left XX Century Fox and didn't sign any new contracts with any of the studios.

The industry became agitated. This was unheard of: not a drug addict, not an alcoholic, not a psychopath, not a schizophrenic, not a communist from the "blacklists"—a solid professional at the peak of his career at age 36 voluntarily leaves Hollywood! Why? Or rather, for what?

Not a bad setup, right?

It's hard to imagine anything more internally contradictory than the California film industry. Few people know that Hollywood arose as a "pirate" republic.

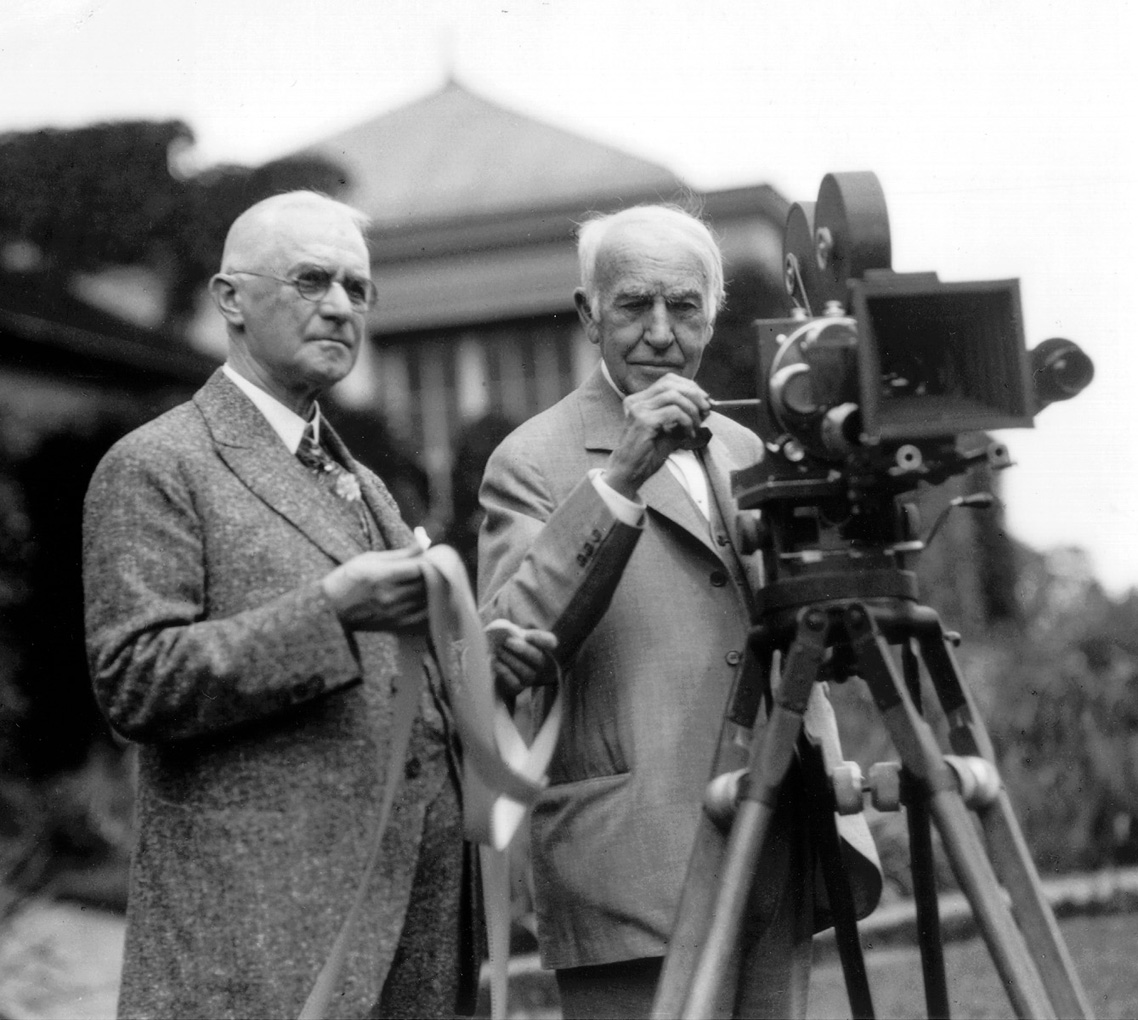

At the beginning of the 20th century, everything in the American film world was done through a "single window" principle. Most films were shot in New York and New Jersey. There were no film studios as such yet, and any American film crew had to rent or buy a patented movie camera from the company of the great inventor Thomas Edison. And load it with patented Eastman Kodak film. Then sell the finished film and copyrights to Motion Pictures company, owned by the great inventor Thomas Edison.

Any American cinema of that time had to purchase a projector or rent it from the company of the great inventor Thomas Edison.

If the cinema, in addition to purchasing the projector, also wanted to show movies, it had to rent copies of the film and purchase screening rights from the Motion Pictures company of the great inventor Thomas Edison.

Why so, you ask? Because the great inventor Thomas Edison had patented the movie camera design, the projector design, the lighting device design, the incandescent lamp design, the filming technology, and the screening technology.

Incidentally, the era of early silent cinema is mistakenly considered an era of black-and-white cinema: the films were mostly in color. The first color film was released in 1895. The colorization technology for monochrome film was developed and implemented by the great inventor Thomas Edison.

The only (rather weak and almost fictitious) competition to the great inventor Thomas Edison could come from one company—Biograph, which had patented an alternative camera design. There were also the French (Pathé) and other Europeans, but the duopoly of Motion Pictures and Biograph was monolithic.

All directors and all distributors had to pay money to either Biograph or the great inventor Thomas Edison, alternately tasting either horseradish or radish. This state of affairs absolutely did not suit filmmakers and cinema owners.

By 1910, numerous "pirate" film crews had gathered in Southern California. They used "gray" equipment, sold their films for "gray" screenings in cinemas, didn't pay royalties, and didn't sell their works to the great inventor Thomas Edison or his small competitor.

They all risked being transformed from comrades of the camera invented by the great inventor Thomas Edison into neighbors in the jail cell that the great inventor Thomas Edison passionately wanted to lock them all in.

Why did Southern California specifically attract independent cinema? Mountains-sun-ocean? Yes, but no. There were two other reasons.

First, California was located as far as possible from Motion Pictures headquarters in New Jersey, and as soon as the patent attorneys of the great inventor Thomas Edison, accompanied by private detectives, boarded a train, the duplex telegraph (patent also belonging to the great inventor Thomas Edison) would sound the alarm, and all the illegal filmmakers with all their equipment and film would flee to Mexico, while local cinemas would temporarily stop showing non-kosher products.

Second, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in California flatly refused to rule in favor of the monopolist from New Jersey.

Lawsuits from both sides multiplied, and finally in 1915, the great inventor Thomas Edison was stripped of a significant number of his patent privileges.

Thus the Hollywood Sich transitioned to legal status and began the process of years of settling down.

And now we need to go back to Europe.

In 1906, a network of train station cafés and confectioneries flourished on the Vienna-Lviv railway line. Along with the network, its owners prospered—the married couple Max and Genia Wilder, who on June 22 of that same year had a son Samuel. Samuel was born at the Sucha Beskidzka station, closer to Zakopane.

The family prospered in Krakow, but in 1914 the Wilders moved to Vienna, and soon the couple divorced.

In Vienna, Samuel finished school and in 1924 enrolled at the university. Wilder so craved journalistic activity that he dropped out of school, falling short of a diploma by literally just three years.

Having almost a whole semester of education at one of the best universities in Europe under his belt, Samuel got a job as a reporter-interviewer at the tabloid Die Stunde ("The Hour").

His first major success was an interview with Professor Freud. Wilder entered the hallway, handed his card to the maid, briefly glimpsed part of the room and the famous couch, and soon the master of the apartment himself appeared in the hallway. Freud made Samuel introduce himself again, inquired about the purpose of the visit, and, as if looking through time, made a prophetic statement: "The door is in front of you." Wilder politely said goodbye and cleverly disappeared, quickly fulfilling the prophecy.

After such a "triumph," something had to be decided, and Samuel decides to flee to Berlin.

In Berlin, far from the parental home and financial support, without any profession (including journalistic), young Wilder went to work as a taxi. Not in a taxi, but as a taxi.

In nightclubs, visitors bought dance tickets and chose a paid partner for one dance, after which the ticket was "punched," and they had to buy another one. Or move from dancing to more profitable pastimes. This is not like turning a steering wheel. In Berlin of those years, this was called "taxi."

Most of Samuel's clientele were women... Of course, this wasn't what papa Max and mama Genia had dreamed of, but what could be done?

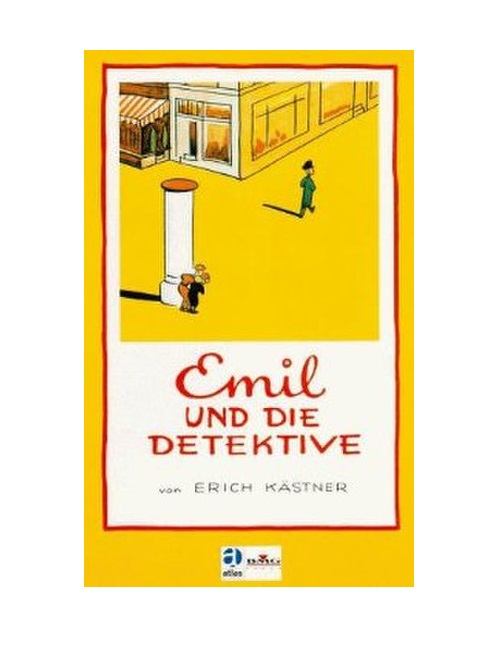

While taxiing in the evenings, during the day Samuel worked as a reporter for several newspapers, and he also made acquaintances in the film world, wrote dozens of mini-scripts for short films, and became co-author of the screenplay for the sensational 1929 film "People on Sunday." His next work was adapting the popular adventure novel "Emil and the Detectives": the film based on his screenplay came out in 1931 and was also successful. Following success came the first money.

Film life in Berlin of those years was rich and interesting (UFA studio, Ernst Lubitsch, Marlene Dietrich, and all that). But simply living in Berlin of those years became dangerous to life.

In 1933, Wilder moved to Paris and debuted as a film director. His first work did very well in French distribution.

Meanwhile, all his Berlin film friends were moving to Hollywood. Again, something had to be decided, and in 1933 Samuel came to the USA on a six-month visa and submitted documents to obtain citizenship.

Immigration rules in those times were no simpler than current ones, and after the visa expired, Wilder went to Mexico, where, waiting for an American passport, he spent a whole six years. He studied English and wrote screenplays for his Berlin film friends who had established themselves in Hollywood.

Wilder's screenplays were brilliant, and his second American film—"Ninotchka" with Greta Garbo in the lead role—made money at the box office, and Wilder was nominated for an Oscar for the first time.

Five years later, Samuel had the statuette itself in his hands—actually, two at once, one in each hand—for the film "The Lost Weekend"—best direction and best screenplay.

Meanwhile, fame grew, Oscar nominations multiplied, and the next statuette came after the film "A Foreign Affair" with Marlene Dietrich in the lead role.

Having lost contact with his parents who remained in Europe, in 1945 Samuel made a film in German for a German audience in memory of them—"Death Mills"—about concentration camps. Wilder could never find out anything about his relatives and mistakenly believed they perished at Auschwitz.

Only in 2011, after researching Israeli and Polish archives, Wilder's biographer discovered that the family was separated. The mother was killed in Krakow in 1943, stepfather Berl was killed in 1942, grandmother Balbina ended up in the ghetto in the town of Nowy Targ, where she died in 1943, and the father's fate remained unknown.

The loss of his family affected his work: Wilder's postwar films were shot in noir style, and even comedies gave off sadness and sarcasm.

Samuel began to get along poorly with his co-authors—screenwriters. One of them—Victor Desny—even sued Wilder and won more than fourteen thousand dollars for plagiarism and copyright infringement—three hundred thousand in today's prices. This was a serious blow to his reputation. And it was also a signal. But about what?

Wilder thought about it. After thinking, he decided. In 1954, his contract with Paramount studio expired. Without renewing the old contract or signing new ones, he declared himself an independent screenwriter and producer.

So what was wrong with the big Hollywood studios?

Drinking binges, suicides, nervous breakdowns, hospitalizations in psychiatric clinics were and remain the norm of the working days of cinema. And whoever drops out of the race, a worthy replacement is already waiting patiently in the long queue at the gate.

Someone's screenplays never made it to screen, someone's faces never went beyond extras, second-tier actors didn't get leading roles.

Certain young debutantes without merit or experience played main heroines, confused lines, disrupted filming—and nothing. Meanwhile, experienced and deserving artists were removed from long-awaited jobs for minor disciplinary violations and sent on the standard route—through binge drinking and depression to the psych ward.

Directors couldn't replace a bad actress without the producer's nod, left projects, forbade mentioning themselves in credits, lost work, and also took to the bottle.

Hollywood was a terrarium where the most diverse creatures had to coexist—informers and freethinkers, blacks and whites, immigrants and locals, Zionists and anti-Semites, communists and non-partisans—in short, everyone.

Everything was allowed—alcohol, drugs, intrigues, scandals, unbridled sex life, extravagant public behavior. Meanwhile, the machine worked flawlessly, producing the exact quantity of film-hours of musicals, detective stories, melodramas, and comedies "on target."

The output plan required enormous quantity and maximum unification of plots and types. Simple, bright stories were needed about how a girl in a thirty-five-dollar dress falls in love with an unmarried man in a six-hundred-dollar car, and he proposes and gives her a four-hundred-dollar ring without discount.

Hollywood giants employed dozens of screenwriters. Each time they started work, they coordinated with studio management the theme, number of scenes, number of main and secondary characters, budget, running time, and target audience.

If a screenplay wasn't good enough, it went to the archive. If a screenplay was good enough, it went to the archive. And if a screenplay was brilliant, it went straight to the archive.

The screenwriter worked for a generous salary but had no rights to his own text: the screenplay belonged to the studio. Proposing a screenplay outside the studio was impossible.

Each studio had a giant supermarket of screenplay works: fatal love in Argentina, mysterious murder in Cairo, intrigue on Wall Street—anything, about anything, and ready for filming.

Films had to be released in dense flow on a clear schedule and look as much like each other as possible. This is now called counter-programming.

The thing is, on average, one picture out of seven was (and is) a box office success. Six pictures out of seven are unprofitable. But that "seventh" one—it justifies the costs for itself and the previous six and the next six, with change left over.

The grim everyday life of the Great Depression drove millions of people to cinemas; there was no other accessible cultural leisure then. Not everyone could afford radio receivers, restaurants, philharmonic halls, and theaters, and television had just appeared and cost more than a car.

For Hollywood, the Great Depression turned into the Great Expression. Money flowed like a river.

The other side of the coin was the creative dissatisfaction of hundreds of people. Actors, directors, screenwriters, musicians drank themselves to death, went mad, hanged themselves, but there was nowhere to go from the system. Beyond Hollywood's gates was "outer space."

Moreover, the fifties were infamously marked by studio management's fight against communist ideas. Studio censorship worked on a grand scale: not only film fragments or entire films were banned; "on the shelf" went dozens of their authors' names. That's when the term "blacklists" appeared.

All suspected of unacceptable connections and sympathies were deprived of work, access to copyright, and fees. Cubic meters of screenplays lay as dead weight—their authors were on "blacklists." Informing flourished magnificently.

The great composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein ended up on the "blacklists." It got to the point where people came under FBI scrutiny and escaped by fleeing the USA, becoming refugees twice over.

The famous actor and director, laureate of the Cannes Film Festival, Jules Dassin, son of an Odessa barber Shmuel Dosin, founder of the noir genre, left the USA to escape prison. He was "betrayed" by the son of an emigrant from the village of Buryakivka (now Ternopil region), the remarkable director and noir colleague Edward Dmytryk, who gave testimony to an FBI commission.

Dmytryk was an outstanding director who had himself been in the Communist Party, exposed fascism and anti-Semitism. For his views, he was not just excommunicated from Hollywood through "blacklists," but sat twice in American prison—six months and a year. He himself was forced to leave the USA and move to Great Britain.

Then he was offered a deal—testimony against Dassin in exchange for exclusion from the "blacklist" and a "pass" back to Hollywood. The director whose films starred Marlon Brando and Brigitte Bardot, Kirk Douglas and Gregory Peck, "broke" and did what was required of him.

The Dassins, thrown out of Hollywood, moved to Europe. Their son Joe became a famous singer, performing songs by Toto Cutugno.

Wilder was one of the first to break through the fence. And the system quickly arranged and won a lawsuit accusing him of plagiarism.

On one hand, everything was lovely: the bag under the bed was stuffed with US dollars, the shelf above the bed groaned under the weight of Oscar statuettes, brilliant ideas wandered in his head and lay on paper, there were no plans to drink himself to death or intentions to hang himself, the FBI had no complaints. Moreover, in that year Wilder was working on two pictures at once—a detective based on an Agatha Christie novel with Marlene Dietrich and a heroic saga about Charles Lindbergh.

But on the other hand, things were terrible. Wilder thrashed about, standing with one foot in Hollywood (the Lindbergh film was being distributed by Warner Bros studio) and the other foot outside the fence (the detective was being shot by an independent producer for an independent distributor). Working on two fronts sent contradictory signals across the front line in both directions. He had to choose whom to stay with. But there was no one to choose from. Wilder was a universal soldier: he produced competently, wrote excellent screenplays, and was a great director. He was his own studio. But he needed another just like himself nearby. And where could he find one?

In such a situation, one could only seriously count on a miracle or a fairy godmother. Other plans and hopes were less realistic and not entirely convincing. Something had to be decided.

Everyone who doesn't believe in miracles and fairy godmothers is asked to stop reading immediately.

We'll ask the rest to turn down the sound on their TVs and after a pause report: in 1955, Wilder found one such, called her, invited her to a meeting, and made a proposal. Then a miracle happened: the fairy agreed.

And what she agreed to was this: Wilder decided to film a French bestseller—a novel by Claude Anet—a cleverly twisted story of an inexperienced girl from high society who decided to pretend to be an experienced married woman and play at adultery with an adult womanizer but due to inexperience suddenly fell in love and married him. A good story.

The plot was a "bomb." But this "bomb" had to be assembled, loaded onto a plane, delivered to the site, and dropped precisely on target.

So who was this fairy godmother who believed in Wilder's idea, served as co-producer and co-author of the screenplay, helped attract investment, persuaded them not to cast Yul Brynner for the lead role (hero and creator of the famous "Magnificent Seven," native of Vladivostok and adopted son of Moscow Art Theater actress Ekaterina Kornakova), convinced them to take on a third picture simultaneously with the previous two, and ultimately got a blockbuster for the ages?

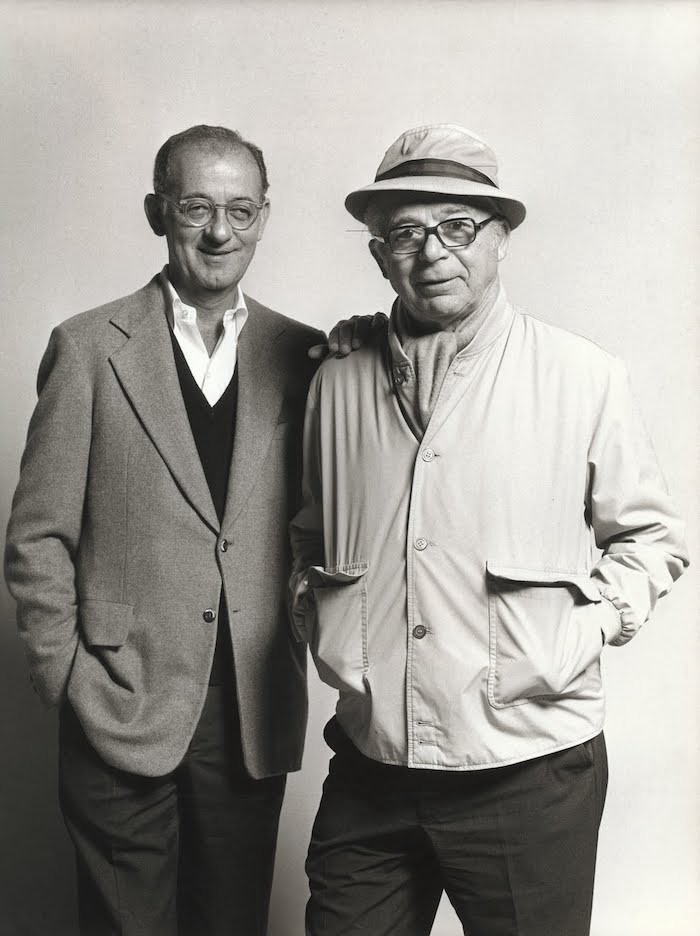

Ladies and gentlemen! Meet them standing: talented journalist, excellent screenwriter, independent producer, and winner of seventeen math olympiads—Izzy Domnich!

Now there were two real wild ones. Former "insiders" who had climbed the entire ladder from bottom to top, respected and loved by all, knowing all the exits and entrances, Sam and Izzy went to battle against the system on its field and in dangerous proximity to it.

They knew their business, and their "bomb" exploded where it should, how it should, and when it should. The year was 1957, and this was "Love in the Afternoon" with Audrey Hepburn and Gary Cooper!

Domnich and Wilder became the most successful operators of the "anti-studio" business model—the independent production and project freelance model, where everyone benefits.

While the "studio" model was spreading seven eggs across seven baskets, "Love in the Afternoon" raked in money at the box office, showing that an independent producer works better. And if only "Love"! All three films ("Witness for the Prosecution," "The Spirit of St. Louis," and "Love in the Afternoon") were released in 1957, harvesting good returns in the USA and excellent ones in Europe. Moreover, "Witness for the Prosecution" was nominated for an Oscar in five categories.

Need we say that the film didn't receive a single statuette? Colleagues looked at "workaholic" Wilder not as a production leader but as a collective farm looks at locusts.

The artistic level of his pictures was higher, box office returns higher, production costs lower, author fees higher, and lifespan in distribution longer.

In his concept, everything was different: no story about "the girl next door" in a thirty-five-dollar dress. Audrey Hepburn's costume designer was Hubert de Givenchy. Marlene Dietrich in Wilder's films was dressed by Coco Chanel and Christian Dior.

In the new model, authors and key performers bore all the risks themselves. Now everyone had a voice and wasn't separated from each other and from the box office by a Great Wall of China made of producer and studio. So why were six "production" pictures needed when you could immediately shoot the "seventh"?

If this wasn't Los Angeles but Las Vegas, it would turn out that Domnich and Wilder had opened a new type of casino—with proven win probability and profitability seven times higher. Well, where would the public and investors rush?

The massive success of an extra-systemic producer could be the beginning of the end of the business model of the entire studio industry.

The bad example could become very contagious: after all, the independent producer had an excellent personnel reserve with a big discount and in an assortment no worse than the studio's—"blacklists."

For Hollywood, this situation was far more dangerous than a visit from the patent attorneys of the great inventor Thomas Edison. The big studio bosses often went to the movies, on both sides of the screen, and understood perfectly well that any triumph could be an unthinkable alignment of astrological circumstances.

Gathering around the calendar, the bosses calculated that from Sam and Izzy's first meeting to their first triumph took about two years and set the big Hollywood alarm clock for 1959.

If "Love in the Afternoon" turned out to be a "bomb," now our two decided to create a super-bomb and detonate it right at Hollywood's gates. Izzy again wanted more, and something had to be decided.

The path chosen was mathematically precise and extremely paradoxical. Domnich and Wilder conceived creating an absurd farce and grotesque, assembling a puzzle from pieces of parodies of old Hollywood hits.

Sort of like "Old Songs About the Main Thing," but not boiled in rose soap, but medium-rare, with blood and very well peppered.

The theorem of Sam and Izzy was drawn ideally and invulnerably: old recognizable characters create a gravitational field, and new characters use the created pull to accelerate interest and for unthinkable breaks in the plot line trajectory.

The mockery of Big Hollywood was being prepared on a massive and deadly poisonous scale.

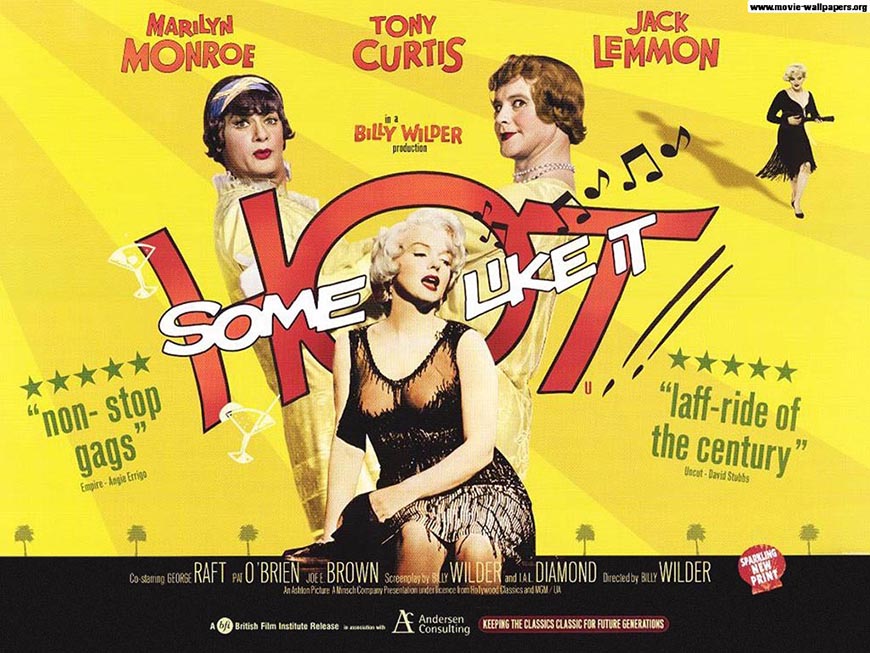

The film's genre was decided to be undefinable: not a musical but with singing and dancing, not a detective but with gangsters and police, not a comedy but madly funny, not a melodrama but about love and jealousy, not an action film but with shooting and corpses, not erotica but with powerful and ambiguous sexual subtext, not social satire but about wealth and poverty, not a thriller but with scenes you want to watch with your eyes covered.

In short, a grandiose mystification was planned.

Supporting characters create the drive and atmosphere of a good film. The film's atmosphere is a super-mission, and therefore you can't make a good film even in California without the right supporting cast.

When the lead roles don't require well-known faces and superstars, Young talent and energy, temperament, reliability, diligence, and precision were needed here.

But a problem arose: the "real" leads—even superstars—would easily dissolve to complete invisibility in the aura of the famous diva.

And then our two captains made a "doubly Solomonic" decision—to constantly swap the first and second planes and, moving from scene to scene, quickly raise the status of the "atmospheric" heroine—Marilyn's name on the poster cost too much.

So what was this reversal, farce, grotesque, satire, thriller, musical, and detective?

By the way, if until now we've been calling Samuel Wilder strictly by his passport, the film industry and viewers know him by his pseudonym in the credits. Let's welcome him standing again: the great Oscar winner—Billy Wilder!

Well, now it seems everything is clear? Ladies and gentlemen! Marilyn Monroe, Jack Lemmon, and Tony Curtis in the film "Some Like It Hot"!

Whistles, amazement, applause.

Those who suddenly understood everything at once are asked not to rejoice prematurely.

The well-known film is called completely differently. And its title contains many diverse hints. Here too there were mystifications and mysteries.

For example, in Central Committee and Council of Ministers resolutions on allocating currency to purchase the picture, a different title appeared—"Some Prefer It in Tempo."

The original film title is "Some Like It Hot." And this phrase isn't entirely simple. "Some like it hot"—who wants it hot, or someone likes to heat things up.

Why did this phrase specifically become the title? Yes, it sounds in the film, and that's first. There's also a second reason: at least two jazz compositions are named this—by Sammy Masters and Gene Krupa. Third, that's what a 1939 musical comedy starring Bob Hope was called. Fourth, in the Mickey Mouse cartoon ("Mickey and His Steamroller"), Minnie Mouse clapped her hands and sang a counting rhyme that included these words: "Some like it hot."

This counting rhyme, however, has an alarming and mystical double bottom and is an encrypted greeting from good old England.

John Newbery's poem "Pease Porridge Hot" from the children's collection "Mother Goose Songs," published in 1760, doesn't repeat but is based on an old (and still popular) scary counting rhyme, quite suitable for use in thrillers and detective stories instead of the counting rhyme about ten little Indians. Here it is in full:

Pease porridge hot, pease porridge cold,

Pease porridge in the pot, nine days old;

Some like it hot, some like it cold,

Some like it in the pot, nine days old.

Translated:

Hot pea porridge, cold pea porridge,

Pea porridge in the pot, sitting nine days.

Someone likes it hot, someone likes it cold,

And someone—from the pot, sitting nine days.

If you read this text about nine days in English in a melancholic child's voice to the sound of a bell and the noise of rain and a wet garden, while the camera prowls in the twilight in damp fog over the outlines of gothic architecture entwined with ivy, you can quite honestly come to cinematographic horror—an excellent Hollywood state. And it's quite suitable as a film title whose genre is conceived as undefinable.

Both Domnich and Wilder were educated and erudite gentlemen. And they could quite consciously hint simultaneously at Walt Disney, Bob Hope, popular jazz performers, and John Newbery.

The screenplay had written on it "Not Tonight Josephine!"—at that time the jazz composition "Yes Tonight Josephine!" was very popular. As a result, there's no Josephine in the title. Although such a phrase is in the film, and in quite a piquant context.

As for the plot basis, here Diamond and Wilder entered into polemic.

Domnich wanted to use the American comedy "Charley's Aunt," released in 1941 when Izzy was taken to Hollywood, and devoted (you don't say!) to the arrival in London of Donna Rosa d'Alvadorez from sunny Brazil, where there are many, many wild monkeys in the forests. Although, to be honest, in the original play staged in 1896, Donna Rosa was called Donna Lucia. And instead of monkeys, there were nuts: "I am Donna Lucia D'Alvadorez from Brazil where the nuts come from." In English, "going nuts" means "going crazy," and the English presentation of Aunt Lucy actually meant "I'm Donna Lucia from Brazil, where the madness comes from."

For Wilder, the film's framework was more of a nod to the work of his old Berlin acquaintance Robert Siodmak—a German remake of the French comedy "Fanfares of Love." According to Wilder, the film itself was "third-rate and terrible," but the idea was workable. Such was the porridge.

In the end, Wilder won: he was fourteen years older, after all...

To avoid any insinuations and considering the "plagiarist" trail that followed Wilder, the authors of the German remake screenplay were indicated in the credits, and they were paid a fee.

The scene in Polyakov's music agency with very ambiguous remarks and comments in Yiddish was changed in the finished screenplay. In 1958, musicians were on strike in Hollywood, and Domnich and Wilder didn't stay on the sidelines and decided to remind them of this.

Other mysteries relate to the film's distribution in the USSR. How Monroe's character became "Dushechka" (Sweetheart), only God knows. In the original, she's officially called Dana Kowalczyk, her full nickname is Sugar Kane—that's sugar cane or "candy cane" (a popular sucking candy in America at the time), and her short nickname is Sugar, which just means "sugar."

As for the song:

I wanna be loved by you, just you

And nobody else but you

I wanna be loved by you, alone!

Boop-boop-a-doop!

...if adequately translated into modern song-erotic language without losses, you could get something like:

"I want you love me, only you!

I no need nobody except you!

I want you love me, you only!

Damn-it-all!"

But such filigree translation work would require many years of labor by a cohesive group of experienced linguists. Well, and dubbing Marilyn's singing with such text would be quite difficult...

And in general, it must be noted that in translation from American to Soviet, the film lost ten percent of its running time, sixty percent of its charm, and was completely deprived of its "double bottom."

But Soviet audiences, not spoiled by witty and sophisticated pictures featuring Marilyn Monroe, were delighted even with what remained.

In Vasily Aksyonov's novel "In Search of Sad Baby," a Baku taxi driver reports to a passenger after viewing: "My wife and I have lived for ten years. We live well... And what did my wife answer? If that actress... comes here, I'll tell you myself: 'Tofik, go!'"

Of course, even with ultra-precise semantic translation, Baku taxi drivers would have had difficulty catching hints at John Newbery's poetry, but sailors would have appreciated the mention of the "storm cellar" in the yacht date scene.

And although the translation and dubbing of the Soviet version were done professionally and delicately, and they wisely didn't translate or re-voice the musical numbers, it's still highly recommended to learn English thoroughly and watch "Some Like It Hot" as is. Preferably with subtitles. And preferably more than once.

Now we need to go to the filming set. In spring 1958, Domnich and Wilder set out on the big trail of big war. They assembled a super-squadron: they needed aces, "stars," and shot-down planes. They weren't going to fight with a construction battalion.

The great Saul Bass, who had just developed the "Kinetic" font for Hitchcock's "Vertigo," was responsible for the titles.

One of the most famous composers and conductors of that era—London native Adolph Deutsch with his orchestra—was invited to write and perform original music.

Matty Malneck's orchestra was brought in for arranging and performing old hits.

The screenplay was written with an eye toward cost savings. The pavilion had to be used to the maximum: hotel interiors, yacht interiors, train interiors, garage interiors, Signor Mozzarella's cheerful funeral home, and the "station" in Chicago.

As for location shooting, it was minimized and conducted close to home. The Seminole Ritz Hotel in Miami was brilliantly played by the Hotel del Coronado in San Diego, and the Atlantic Ocean role was magnificently handled by the Pacific.

And an amazing flash mob was devised: it was agreed not to interrupt the hotel's work during filming. Everyone we see in the frame in the background—real guests and real staff of a real hotel who played along with the film crew and dressed in retro costumes. The economics were economical.

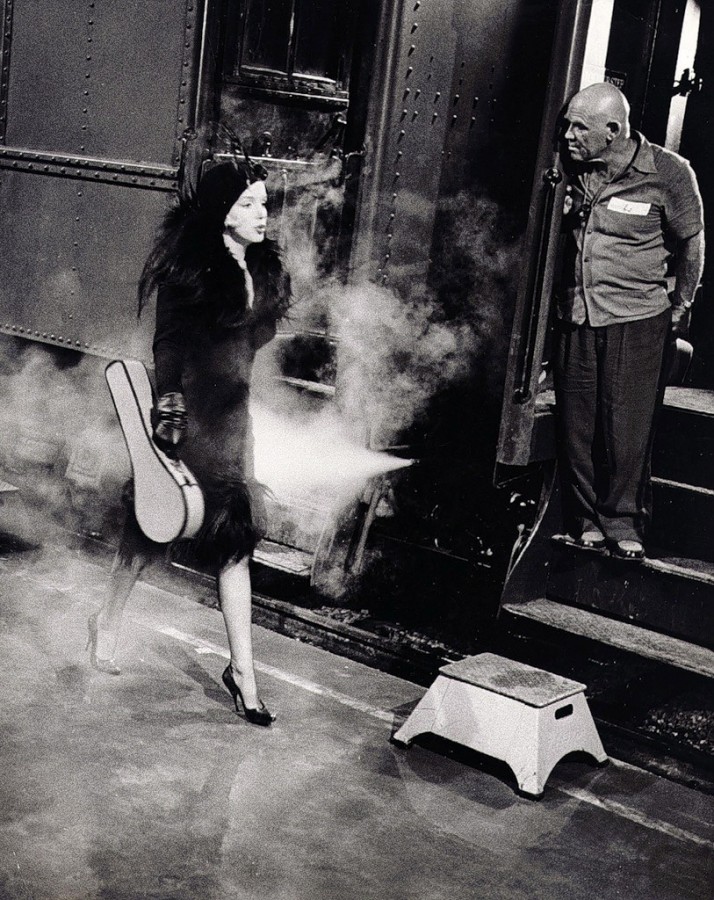

Filming began with the "station" scene—the departure of the "Chicago-Miami" train.

The necessary platform with decorations was only found at Metro Goldwin Mayer studio. That's the one with the roaring lion and "Tom and Jerry." But they weren't burning with desire to help enemies and competitors. And in general, big studios didn't let "outsiders" within a mile of their precious resources.

But Wilder was from Krakow, and the co-owner of Metro Goldwin Mayer—"that very" great Samuel Goldwyn—was actually Shmuel Gelbfish from Warsaw. The superposition was beautiful, they found not just a common language but immediately two (Yiddish and Polish) and agreed about everything excellently.

Incidentally, "that very" great Louis Mayer, who had died the year before, was also neither Louis nor Mayer but Lazar Meir from near Minsk.

And what about Mayer! Warner Brothers were brothers but weren't Warners: their surname was Wonsal, and they weren't called Harry, Albert, Sam, and Jack but Hirsch, Aaron, Shmuel, and Yitzhak.

Columbia Pictures was founded by Harry Cohn, his brother Jack, and their friend—screenwriter Joe Brandt.

Paramount Pictures was founded by Budapest native Adolph Zukor and his cousin Max Goldstein.

Universal Pictures studio was founded by a solid collective from Württemberg: Abe Stern, his brother Julius Stern, and their brother-in-law Carl Laemmle called themselves Yankee Pictures and independently sold their pictures to cinemas, creating in 1912 the first vertically integrated "universal" film company in the industry, becoming the progenitors of the studio model of film business and ultimately destroying the life's work of the great inventor Thomas Edison.

The founders of XX Century Fox studio were Darryl Zanuck (Nebraska native with Swiss roots) and Iosif Sheinker (Joe Schenck), native of Rybinsk in Yaroslavl province. Iosif's father, Chaim Sheinker, was a clerk in the Volga Shipping Company office, and the younger brother "pulled over" the whole family to New York and persuaded them to take a concession on one of the first amusement parks.

Truly, Hollywood is a land of mystifications.

In short, Wilder and Domnich suddenly and inexpensively through connections got a magnificent platform with the necessary decorations. The economics continued to be economical.

But the decoration wasn't the only problem. The station scene was the first where instead of Joe and Jerry appeared Josephine and Geraldine. And they were unhappy.

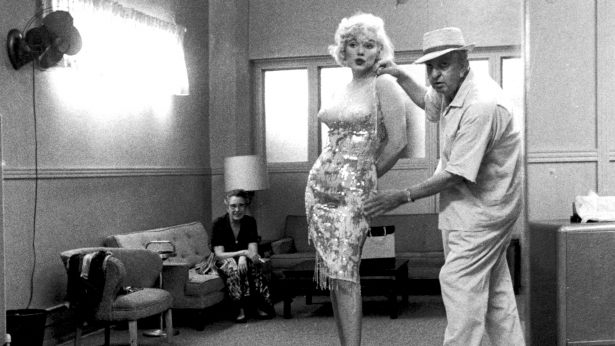

Lemmon and Curtis declared they didn't like the styles of their dresses. And the men also reported they liked Marilyn Monroe's dresses and wanted the same. An expedition was immediately dispatched to her fashion designer—Australian Orry-Kelly. Kelly, though already an alcoholic binge drinker, enthusiastically took up the work and instantly "constructed" a series of elegant dresses, creating an exquisite costume ensemble in each episode.

Curtis was very pleased with the new dresses: after all, he had started his career as a tailor in a fashionable atelier. And by the way, he also wasn't Curtis or Tony. He was Bernard Schwartz. The Schwartz family arrived in New York from the town of Mátészalka, about a hundred kilometers from Uzhhorod. Oh, that Hollywood...

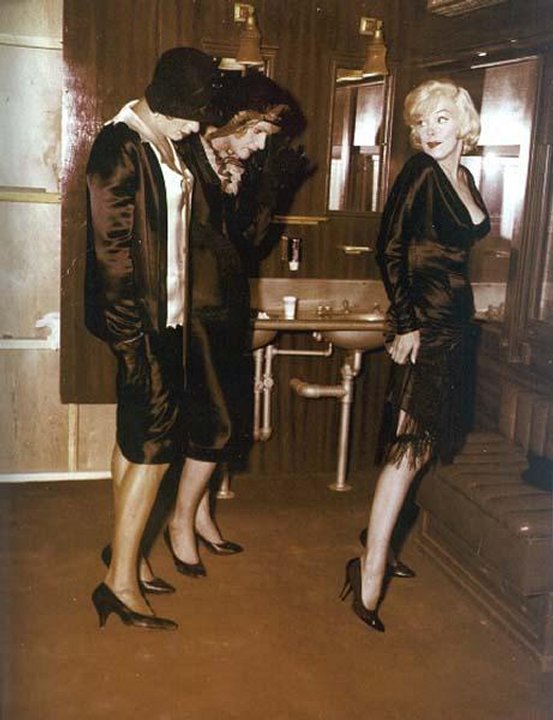

Then Curtis and Lemmon in their new costumes went "on reconnaissance" to the women's restroom in a neighboring pavilion. The visit to the women's restroom ended in embarrassment. Wilder ordered the guys: leave the restrooms as they are; don't go to the women's restroom.

One of the main mystifications of the project, and of Hollywood in general, was that "the planet's main blonde," who became the blonde standard—the blonde that other blondes measured themselves against and tried and still try to imitate, the blonde who developed and implemented the blonde image, blonde behavior model, and even "blonde logic"—wasn't actually a blonde.

Marilyn Monroe (or rather, Norma Mortenson) had beautiful chestnut hair. Her natural beauty is wonderfully captured in early color photos. But what are these photos? It turns out that in 1946, twenty-year-old Norma caught the eye of a professional photographer who had come looking for models for calendars among "production shock workers."

And Mortenson really was a "production shock worker." A real one! And the production wasn't simple. Not at all simple. The future superstar worked on a secret assembly line at the military Radioplane Co. factory. And she assembled (think about it, in 1946!) unmanned aerial vehicles. Drones! In 1946, the US Army already had radio-controlled combat and reconnaissance aircraft.

So, the young assembler caught the eye of army photographer David Conover, who offered her quite a solid fee for those times—from 5 to 7 dollars per shoot. Thanks to that very shoot, professional photos of the future Marilyn appeared.

The miracle of transforming a brunette into a blonde was repeated weekly, and it was quite a process. This process is described in detail in the memoirs of French cinema star Simone Signoret, wife of Yves Montand. Two "star" couples—Miller-Monroe and Montand-Signoret—lived in California as neighbors and were friends for a long time.

The heroine of Signoret's recollections was an unnamed cinema veteran who once handled the hairstyle of Marilyn's idol and inspiration—Jean Harlow, who died tragically at a young age.

Every Saturday, Marilyn's chauffeur would meet a flight from San Diego. The flight brought the bleaching guru. With the guru came a "laboratory" in two suitcases. The chemical experiments took from two to four hours, after which Monroe was again ready for a week's work in front of the camera, and in a week the "laboratory" and "laboratory assistant" would arrive to renew the effect. Marilyn refused to work with other specialists: the result wasn't the same.

Besides the hair lightening specialist, the super-diva was cared for by an entire brigade of pros: acting teacher (the famous Paula Strasberg), voice teacher, psychoanalyst, ballet master, and costume designer—Orry-Kelly.

A very smart and competent team worked on creating the screen star's image. According to colleagues' recollections, Marilyn was an extremely systematic and disciplined performer who precisely followed the instructions of her mentors and curators.

However, she also had to follow the director's instructions, the studio choreographer's, the studio vocal coach's, and the orchestra conductor's. Two teams on one set: sparks could fly at any moment...

But sparks weren't needed by anyone—Wilder had heard about Marilyn's conflict with Spyros Skouras and George Cukor and didn't want to repeat Fox studio's mistakes. He was patient and attentive.

Marilyn was also a good girl: she knew the terms of her rental, understood Wilder and Domnich's all-in bet, desperately needed money, worked without a daily fee, counted every minute, every cent, and every take.

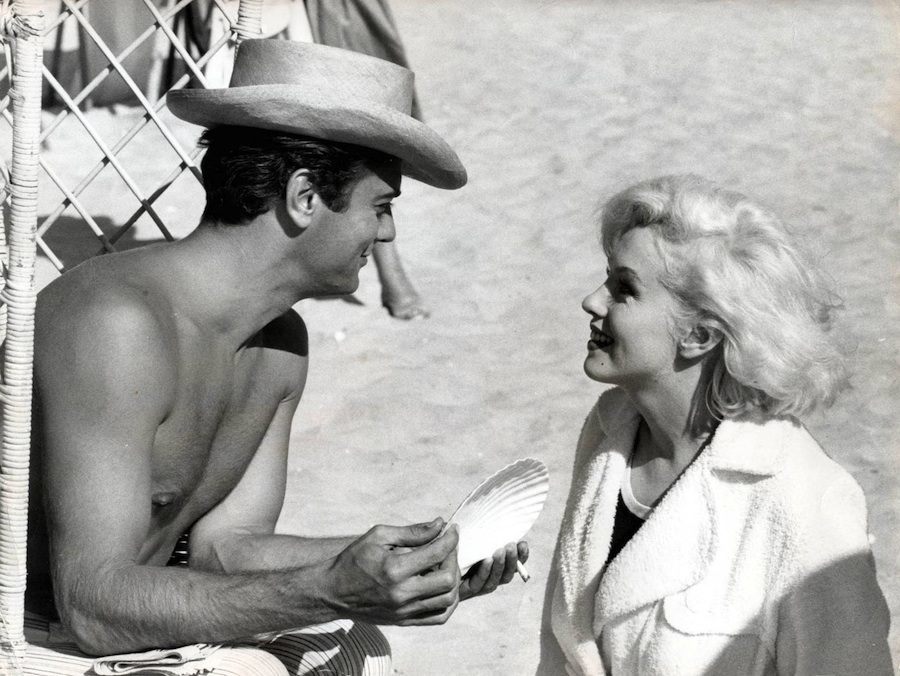

The results of her first weeks of work on set were amazing. In the beach scene where the "billionaire" and "Shell owner" (Curtis's character) met "Sweetheart"-"Sugar," Marilyn had over a hundred lines of dialogue. And this scene was shot in one take! And in general, the entire series of "beach" scenes was shot instantly and brilliantly.

But what was surprising: on one hand, for Wilder such a situation was unacceptable. He never deviated from the screenplay, schedule, or budget. And Monroe leveled all his principles and all his professional habits to the ground.

Wilder described what was happening like this: "We're mid-flight, there's a psycho on board, and he has a bomb." Many in his place would look for an "emergency brake."

But on the other hand, he said something like this: "I remember dozens of cases when actors confused lines, got lost, and didn't know what to do in the frame. Monroe constantly forgets lines, but I don't recall a single case when she didn't know what to do in the frame."

Little by little, the date arrived that the entire film crew remembered: October 24, 1958, work began on the yacht date scene. Everyone's nerves were on edge. Everyone felt lousy, and Monroe had frequent bleeding added to all her previous problems.

It all started with Monroe's charms really working on Tony Curtis exactly as intended, and everything human was so not foreign to him that it was visible and ruined take after take. Now Tony was the problem, extra takes were because of him, and nobody expected such a turn. Wilder and Domnich hadn't planned an adult film.

When Curtis, like Stierlitz, gained control of himself, Monroe would forget the text again, and everyone would start over. Plus, she was often nauseous. Wilder was in despair, and not he alone.

The torments of love lasted about a week. One of the longest scenes was shot only on the forty-second take. When Curtis was asked what it was like kissing Marilyn Monroe, he delicately remained silent or uttered the word "Hitler."

Hollywood also knew about what was happening. And patiently waited for mutiny on the rebels' ship. Something had to end first: either money, patience, or health.

One of the reasons Marilyn Monroe initially didn't want to accept Wilder's offer was her turbulent family life. But she desperately needed money, and at the insistence of her then-husband—the famous playwright Arthur Miller—she agreed to the role of a "dumb blonde who can't tell a man from a woman"—those are her words—and even without an advance, only for future fees and a percentage of box office. The "star" family needed money.

Miller was a man of moods (mostly bad moods). He often came to the set and, without embarrassing anyone, made scenes with his wife. Against the background of an extremely tense schedule and grueling work, these scenes quickly took Marilyn out of working condition and into depression. From anxiety and fatigue, she developed sleep problems. She didn't fall asleep before four in the morning.

This was poor support for the film crew: actors had to arrive for makeup at 5:30 AM, and filming started around eight. After an hour and a half of sleep, and under the influence of sleeping pills, Marilyn couldn't work, couldn't remember lines, she began having episodes of spatial disorientation: once she missed a shooting day, reporting that she couldn't remember where the set was located.

Day after day, Monroe lost the ability to work: she was "giving up" morally, physically, and mentally. Now any scene was an insurmountable obstacle: Monroe almost couldn't memorize lines, but spent a long time arguing with the director, constantly demanded reshoots and additional takes. She herself didn't communicate with anyone, and all negotiations were conducted through her coach—Paula Strasberg.

On nervous grounds, Wilder began having severe back pain. Every missed shooting day cost him and Domnich a round sum: all the money was their own.

Against the background of back pain, Wilder himself stopped sleeping and began taking painkillers and sleeping pills. The filming period dragged on, there were no results. The process was heading into a dead end.

Massive screenplay reworking began. All long phrases were removed. Episodes with Monroe were broken into short parts. Lines were either removed or shortened. But if Monroe's lines became rarer and shorter, her partners' lines lengthened and multiplied, and everything had to be relearned on the fly; nervousness grew.

To one day due to the actress's unforeseen absence (she was now called not Missis Monroe but Missing Monroe), filming of the song scene "I wanna be in love" was under threat. About 200 people had been hired for the crowd scene, but there was no performer.

When she was finally found and brought in, she was in a depressed state, under the influence of alcohol and sleeping pills, and couldn't get up from her chair and leave the dressing room.

Understanding the severity of her condition, Wilder talked to Matty Malneck, and the orchestra began performing the composition, with the vocal part performed by the orchestra's soloist. By the director's idea, hearing "her" song, Monroe should still come out to the set.

Strangely enough, this trick worked, and from the second take, the brilliant musical number was shot. The heroine's emotional state fully corresponded to the performer's depressed mood.

On lucky days, everyone arrived at the set at five in the morning, got makeup until eight, and began work. Marilyn didn't leave the dressing room before six in the evening. On lucky days.

The tricks they now had to resort to resembled attempts to feed a naughty child. And more and more were needed. To everyone's horror, Monroe's condition deteriorated rapidly.

The problem with the actress's mental health was long-standing and familial: Norma's mother was placed in a psychiatric clinic with a diagnosis of "paranoid schizophrenia" and couldn't maintain relationships with her daughter (or with the outside world).

Norma herself, due to her mother's unstable condition, from age nine bounced around other people's homes, living sometimes with an aunt, sometimes with grandmother, and at age twelve ended up in a foster family where a stepbrother tried to molest her. Her aunt (mother's cousin) took her from the foster family, and soon the aunt's partner also attempted to molest Norma.

In those times, all such problems were solved at the expense of children's health and lives. As a result, thirteen-year-old Norma made her first suicide attempt.

After the suicide attempt, the unfortunate girl was taken in by her grandmother. According to Monroe, she spent the two calmest years of her life with grandmother.

Next, Norma tried to change her environment, get a job, and leave California, but legislation prohibited minors from leaving the county without parental or official guardian permission.

Her mother was in a psychiatric hospital, the girl didn't know her father even by name, and turning to official guardians (the foster family where they tried to molest her) was unbearable, so sixteen-year-old Norma decided to get married—this was the only legal way to gain at least some freedom and peace. And already married, she could leave and get a job—assembling unmanned aerial vehicles...

Subsequently, Monroe was very interested in Dostoevsky and, alas, not without reason dreamed of playing Grushenka and Nastasya Filippovna...

Is it any surprise what a nightmare her adult life, her work, and the lives of all the people around her were after such a childhood?

By early September, filming had practically stalled: Marilyn developed a fear of the camera, and she tried to drive it away with psychoanalysis sessions, acting classes, sleeping pills, and alcohol.

On September 15, Paula Strasberg arrived for another lesson and knocked on Monroe's hotel room door. There was no answer, so the door was broken down. The actress was found unconscious on the floor and taken to the hospital.

Almost everything was familiar: acute alcohol-drug intoxication, clinical depression, series of panic attacks, suicide attempt... But there was also news: Marilyn was five months pregnant.

Wilder wanted farce and grotesque on screen? Reality turned out more absurd than any screenplay.

Well, what could be done? What could be done? Marilyn spent two weeks in the hospital. Filming continued.

All the props were now covered with "cheat sheets." Monroe's lines were written on slips of paper and in pencil on all objects in her field of vision. This is especially visible in telephone conversation scenes: there's no partner in frame, and the actress's gaze jumps from slip to slip.

In one episode (hotel scene), she needed to say on close-up: "It's me, Sugar!" All variations were pronounced: "It's Sugar me," "Me it's Sugar," "Sugar it's me." Except, of course, the desired one. Wilder suggested writing the text on a cheat sheet. Monroe refused. The number of takes exceeded thirty.

Everyone got angry and tired, and to defuse the situation, Wilder said: "Marilyn, the main thing is don't worry." She replied: "What happened?" And then Wilder needed an injection. To the doctor giving the injection, Wilder said: "Are you sure you have a diploma?" We don't know if the doctor needed an injection.

If from some take they managed to capture hitting most of the lines, they moved to the next episode.

The actress's figure was "rounding," and they used a girl from the orchestra as a double—Sandra Warner. Sandra was taller but had similar proportions and fit into all Monroe's costumes. For shooting promotional posters with full-length photos, they used only Sandra. Monroe herself could now only be shot in close-up or above the waist.

They took advantage of Marilyn's moments of immobility during her alcohol or drug-induced sleep to apply makeup: at other times she was in a state of motor disinhibition and couldn't "freeze" for long.

There was no point talking about Wilder's condition: he was on sleeping pills and painkillers.

Next in line for a nervous breakdown was Tony Curtis. He absolutely wasn't ready to take the hit: because of his partner's antics, he had to do dozens of extra takes, waste time, wait for hours, constantly concentrate. He also began taking sedatives.

But what was surprising: on one hand, for Wilder such a situation was unacceptable. He never deviated from the screenplay, schedule, or budget. And Monroe leveled all his principles and all his professional habits to the ground.

But on the other hand, he said something like: "I remember dozens of cases when actors confused lines, got lost, and didn't know what to do in the frame. Monroe constantly forgets lines, but I don't recall a single case when she didn't know what to do in the frame."

Gradually the date arrived that the entire film crew remembered: October 24, 1958, work began on the yacht date scene. Everyone's nerves were on edge. Everyone felt awful, and Monroe had frequent bleeding added to all her previous problems.

It started with Monroe's charms really working on Tony Curtis exactly as intended, and everything human was so not foreign to him that it was visible and ruined take after take. Now Tony was the problem, extra takes were because of him, and nobody expected such a turn. Wilder and Domnich hadn't planned an adult film.

When Curtis, like Stierlitz, gained control of himself, Monroe would forget lines again, and everyone would start over. Plus, she was often nauseous. Wilder was in despair, and not he alone.

The torments of love lasted about a week. One of the longest scenes was shot only on the forty-second take. When Curtis was asked what it was like kissing Marilyn Monroe, he delicately remained silent or uttered the word "Hitler."

Hollywood also knew what was happening. And patiently waited for mutiny on the rebels' ship. Something had to end first: either money, patience, or health.

The complex filming schedule, constant stress, alcohol and sleeping pill abuse led to Monroe's pregnancy not ending in childbirth. Marilyn was exhausted, her condition wasn't optimistic. But she endured both the completion of filming and the period of work in the audio studio.

In general, the patience, trust, and mutual respect of all project participants can only be marveled at. Against the background of big studios with their eternal intrigues and gossip, the fact that by the end of 1958 filming was completed (with an incredible delay of 29 days and cost overrun of about five hundred thousand dollars with a planned budget of two million four hundred thousand) turned out to be a miracle.

By mid-March, editing and voice-over were completed, and the film's creators dispersed to hospitals for treatment. And the film had yet to receive a distribution rating.

For a review, Wilder turned to an organization with a bright name—the National Legion of Decency (formerly Catholic Legion of Decency).

The Legion's head, Monsignor Thomas Little, wrote a review worth quoting in full: "Some elements of the screen adaptation may be regarded as a serious offense against Christian and traditional norms of morality and decency. The film's leading theme is transvestism. Naturally, it is fraught with complex consequences; the film itself contains clear hints at homosexuality and lesbianism. The dialogues are not just ambiguous but openly obscene. The offensiveness of the characters' costumes is also beyond doubt."

Now, after decades, after hundreds of shameful scandals and trials regarding pedophilia and other forms of not-quite-holy behavior by clergy of various ranks, we understand the true state of affairs at that time, and such fiery and narrowly focused erudition of the "decency expert" evokes nothing but mocking irony. But then his opinion and authority meant a lot.

They had to release the film into limited test distribution without an age rating, which could be equivalent to an "adult film" category. Some states delayed the film's release, not understanding what to do with a picture without a rating. Everything about this film's fate was unprecedented...

Now in New York on Times Square at 1540 Broadway stands the Bertelsmann skyscraper. And once upon a time there was one of the most luxurious cinemas in the Loew's State Theatre chain. That's where they decided to hold the official premiere of "Some Like It Hot."

An advertising campaign was conducted, and on March 29, 1959, long before the time indicated on the poster, crowds of people began streaming onto Broadway. They didn't have premiere tickets, but they hoped to see Marilyn Monroe. Soon the number of hopefuls exceeded all imaginable and unimaginable limits, and police units were called in, who had to block traffic both along Broadway and along Seventh Avenue.

Time passed, excitement grew, guests arrived, but Monroe wasn't there. And then this happened: Wilder wouldn't be Wilder, and Domnich wouldn't be Domnich, if on the occasion of the premiere they hadn't tried once more to joke harshly.

Lovers of "hot stuff" weren't disappointed: to the wail of sirens and the roar of the crowd, a fire truck drove up to the cinema, atop which sat the main heroine of the second plan, who was also the main heroine of the first plan. Now they could begin...

In the morning, all the newspapers came out with the film's title on the front pages. Viewers, press, and film colleagues agreed: the film was extraordinary in quality, scale, boldness, novelty, and genre. Everything was executed as intended.

Hollywood chose an extremely unfortunate way to react—it took revenge. But the revenge was petty. If Sam and Izzy's manifesto was brilliant work, then Hollywood's response manifesto was an inadequate assessment of this brilliant work.

The Academy Awards ceremony that year was a demonstration of truly parochial pettiness. It's not that Domnich and Wilder lacked statuettes and nominations—they already had everything. But the industry showed the scale of its solidarity fear: on April 4, 1960, the film received only one Oscar—the statuette went to Orry-Kelly in the "Best Costumes for Black-and-White Film" category.

In the nominations for "best direction" (Billy Wilder), "best adapted screenplay" (Billy Wilder and Izzy Diamond), best cinematography (Charles Lang), best set decoration (decorations by Edward Boyle and production designer Ted Haworth), best leading actor (Jack Lemmon), the film "flew by." Or more precisely, Hollywood "flew by."

The Oscar for best film that evening went to the pompous ultra-Hollywood saga "Ben-Hur," produced by Kiev native Sam Zimbalist, with Metro Goldwin Mayer as the production company. In total, the Gelbfish corporation (which had managed to help our two friends as well) took home 11 statuettes that evening. Hollywood stood solid behind "Ben-Hur."

For the record and fairness, let's report that that evening statuettes also went to Simone Signoret (best actress) and "The Diary of Anne Frank" (best black-and-white film). Incidentally, Monroe wasn't even nominated for best actress: Simone Signoret's company in the nomination consisted of Elizabeth Taylor, Audrey Hepburn, and Katharine Hepburn.

But other awards that year went precisely where they should: Sam and Izzy received the Writers Guild award (for best comedy screenplay, as you might guess), Billy Wilder, Marilyn Monroe, and Jack Lemmon received Golden Globe statuettes that year (association of foreign press with Hollywood)—best comedy actor, best comedy actress, and best comedy or musical.

The National Society of Film Critics recognized "Some Like It Hot" as the best picture of the year, and the British Film Academy recognized Jack Lemmon as best actor of the year. For the film's soundtrack, Matty Malneck and Adolph Deutsch were nominated for a Grammy.

By year's end, the film took third place in box office collections in the USA and burst into leading positions abroad.

The project stayed in mass distribution for about three years and collected forty million dollars (of which twenty-five million in the USA) at a cost of about two million nine hundred thousand. Fourteen to one. Better than "Star Wars." That's approximately a billion dollars in current proportions. For reference: "Pulp Fiction" collected two hundred thirteen million in current dollars at the box office.

Lemmon, Curtis, and Monroe felt truly wealthy for the first time, and for the first two this was also a launch into orbit—now they both went from second-tier comedians to first-magnitude stars.

The big Hollywood alarm clock rang on time, and now the big bosses themselves had to decide something—drink sleeping pills and sedatives or just drink. They were serious people and found no consolation in reading numerous curses and accusations of the film promoting indecency, debauchery, homosexuality, and other "isms."

However elegant the film was and however warmly it was received by viewers and critics, the business model proposed by Domnich and Wilder was no less elegant.

The investment in the picture paid off with a coefficient of 14/1. The picture immediately turned out to be the "seventh," meaning production was "waste-free." The actors' fees were incomparable with the salaries studios paid them: Marilyn Monroe earned 10% of box office amounts exceeding 4 million dollars, Tony Curtis worked for 5% of amounts over 2 million, and Billy Wilder as producer was "subscribed" to 17.5% of the first million, 20% of subsequent receipts, plus he received 200 thousand dollars as director. Don't forget to multiply by 25!

Deferred fees without advances and fixed rates turned out to be unheard of high, and a long line of candidates for lead roles in future films formed for Wilder and Domnich. The reputation of "rebels" and "outcasts" evaporated without a trace: now our two were the dominant trend, and big studios were offered a catch-up game.

Studio pavilions with unique equipment and props ceased to be mysterious caves of Ali Baba and began to be rented out—the achievements of studio artists and engineers became available to the entire industry, including TV people: thanks to Gelbfish and Wilder.

For the first time in American film distribution history, a blockbuster without an age rating appeared on screens. This was unheard of. Equally unheard of was the film's boldness: puritanical American society threw tons of adrenaline from its first major collision with harsh, toxic, and provocative Jewish humor—humor of multi-layered allusions and supersonic speeds, mercilessly witty and endlessly funny.

For Jewish humor in American cinema, this was, to use modern language, an emancipation excess with instant transition to legal status.

The film has not a single scene and not a single phrase without a double bottom (at least in the original English version). Wilder himself said about this: "All ideas penetrated our film illegally. All our humor is contraband."

The film produced a historic shift in the boundaries of the permissible and allowable in American cinema. Studio censors and public figures in the field of decency turned into clowns. The status of studio censorship was officially sent for review.

The most famous film works of new times are, as a rule, products of independent producers—from the American film "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest," produced by Michael Douglas and Saul Zaentz, to the New Zealand "Lord of the Rings," produced by Peter Jackson and Saul Zaentz.

What happened also had an important creative subtext: actors and screenwriters became independent agents, and their new fees allowed them to produce their own and others' ideas. Now there was no need to go on a binge from dissatisfaction: material independence generated a new degree of creative liberation and gave impulse and resources to new cinema.

Without Sam Wilder and Izzy Domnich, neither Miloš Forman, nor Sydney Pollack, nor Woody Allen would have happened.

And what happened to the big studios? They're now part of history. XX Century Fox was "eaten" by Rupert Murdoch's Anglo-Australian magnate's News Corporation empire. The legendary Columbia is now a structure of Sony Pictures Entertainment. Warner Bros entered Ted Turner's media group alongside Time magazine and CNN television network. Paramount Pictures was "swallowed" by internet provider and cable TV operator Viacom, which also owns MTV and Nickelodeon channels. Universal studio together with NBC television company entered Comcast—a provider of satellite and cable internet, IPTV networks, telephone communications, and security alarms. That's all the cinema...

Metro Goldwin Mayer survived, having absorbed United Artists and timely beginning development of its own online content delivery platforms—without involving cinema networks and television networks. The second independent "pillar" is the Walt Disney empire, which was saved from collapse by the legendary Steve Jobs, who initiated an almost friendly merger with the animation giant Pixar he created.

Following the image and likeness of film groups, project teams began to be assembled in other types of business—in construction, in science, in education. The experience of creating and operating a project office has never been honed better than in the film industry. The business processes of film production rhyme beautifully with the algorithms of dozens of other types of project activities.

One cannot bypass attention to the humanitarian component of project freelancing. Since a project team is formed, mobilized, and exists within a deliberately limited period of time, the ability to interact, explain, understand, lead, obey, empathize, make others' priorities your own, and achieve interaction with people who are not formally subordinate to you is as important a part of the profession as the actual acting, directing, musical, writing, composing, and engineering-technical craft.

Non-violent subordination within a team without rigid hierarchy (but with strict discipline and clear regulations) is only possible in an environment of conscious, conscientious, and positively motivated people.

Only in an atmosphere of trust can one work with "irreplaceable" people. Wilder said many times that instead of Monroe, any actress could have been invited who would be easy to replace. But he was being disingenuous: only four candidates were considered—Marilyn Monroe, Audrey Hepburn, Elizabeth Taylor, and Mitzi Gaynor. And it's not entirely clear which of them could have been replaced. And by whom.

The most important property of both Domnich and Wilder was the readiness to risk and go all-in. They left Europe (not today's Europe), and their bridges were burned many times over. Everyday anti-Semitism opened the road to political Nazism, and political Nazism transitioned into the Holocaust and World War and burned all their former life with its café-confectioneries.

Minsk, Kiev, Odessa, Krakow, Warsaw, Sucha-Beskidzka, and Ungeny—Europe long and diligently rid itself of the Gelbfishes, Zimbalists, Domnichs, Malnecks, Wilders, Meirs, and Dassins.

Those who stayed died. And those who left built Hollywood. They developed both the studio model and the project model, and went the entire path from Senator McCarthy's "blacklists" to Netflix's "blacklists."

Having lost relatives and survived only thanks to their mobility and complete absence of conformism, these people didn't know what a comfort zone was. They had nothing to lose or fear and nothing to look back on. They simply went ahead in the company of their own kind.

In 2017, the BBC television company conducted a survey of two hundred fifty-three film critics from fifty countries asking them to name the best comedy in cinema history. "Some Like It Hot" was recognized as the best comedy.

Sam and Izzy created 13 pictures in collaboration. They worked together until 1981. And were friends—until the end of their lives.

Izek Domnich died at age sixty-seven in 1988. Samuel Wilder lived to 2002 and died at age ninety-five in his home in Beverly Hills.

And finally, if your project urgently needs a fairy godmother, look for her among math olympiad winners.

The best phone books in the world aren't the "Yellow Pages" but the "blacklists."

When you see opening credits for Hollywood pictures, don't forget that behind the huge letters, solemn music, orchestras, and fanfares stand talented and desperate people who left their homes and fled to distant America from angry mobs, pogroms, and murders.

If you face a complex revolutionary project that someone must manage and someone must bring to victorious finale, you know how to contact us.

Well, if this text seemed drawn-out, boring, useless, and immodestly self-promotional to you, we apologize, but please don't be upset. After all, everyone has their shortcomings.

Author: Evgeniy Kaganovich